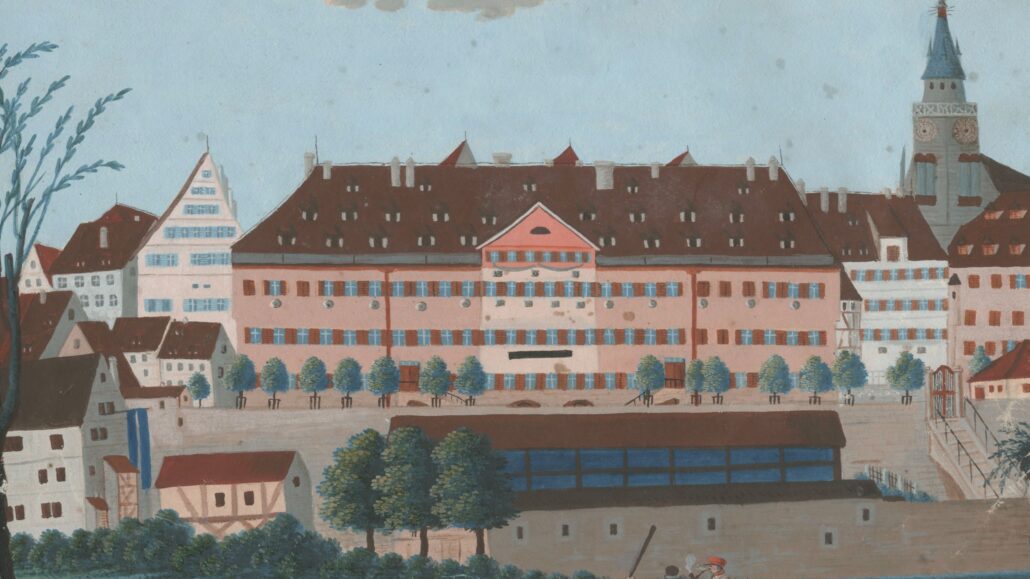

View from the Tower

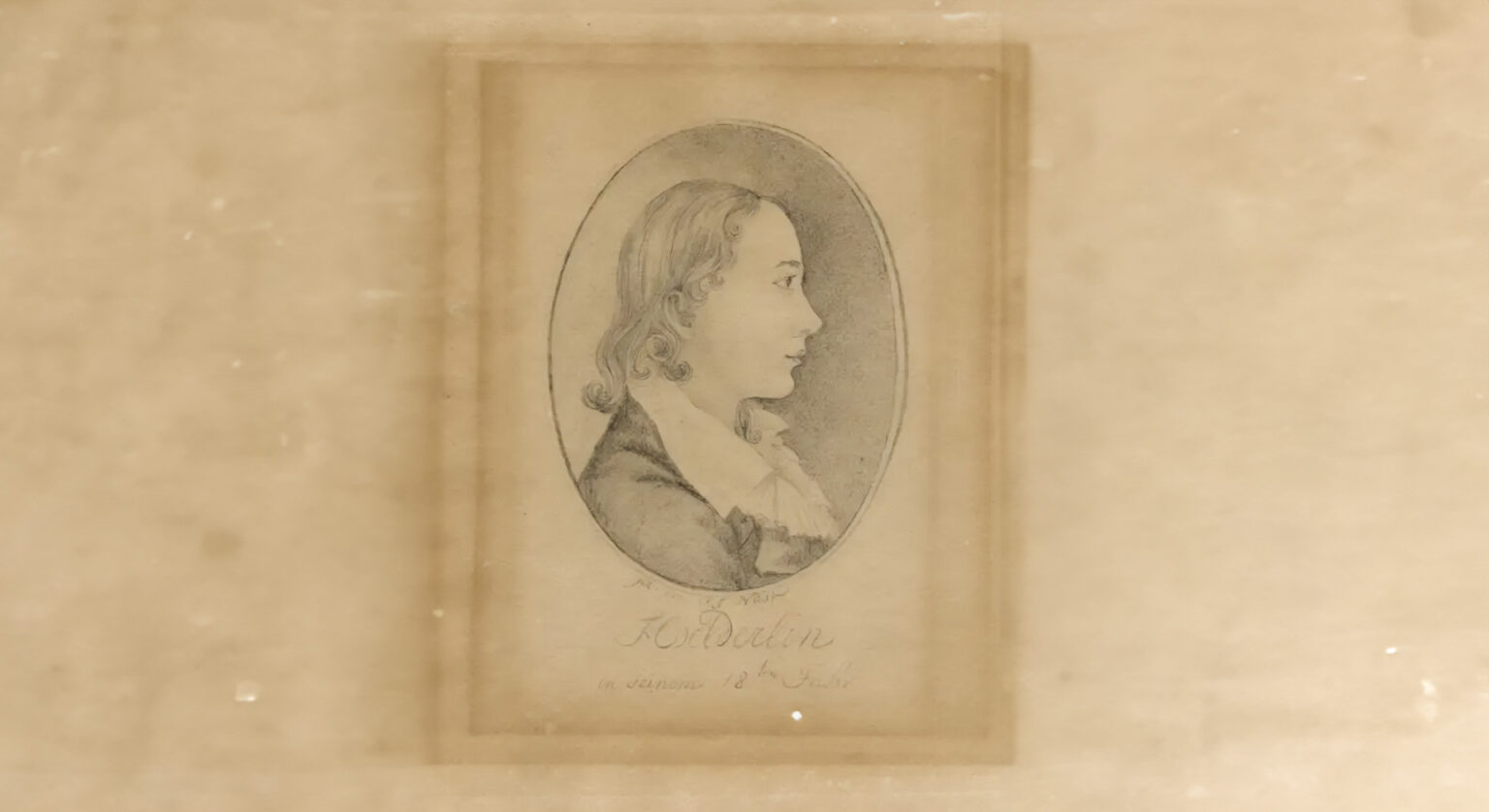

Among the many remarkable stories of Hölderlin’s life is the tale of Ernst Zimmer, a master carpenter who generously took in the troubled poet into his home and family. An ardent admirer of Hyperion, Zimmer offered sanctuary and care to Hölderlin upon his release from the psychiatric institution. From his room, the poet looked out upon an expansive landscape, for the Neckar River was still wild and its current strong. Neither the Neckar Island with its yet-to-be-planted tree-lined avenue, nor the present-day outlook of Tübingen existed at that time.